MARY T. SMITH

MARY

TILLMAN

SMITH

MARY TILLMAN SMITH

b. 1904 — d. 1995

Hazelhurst, Mississippi

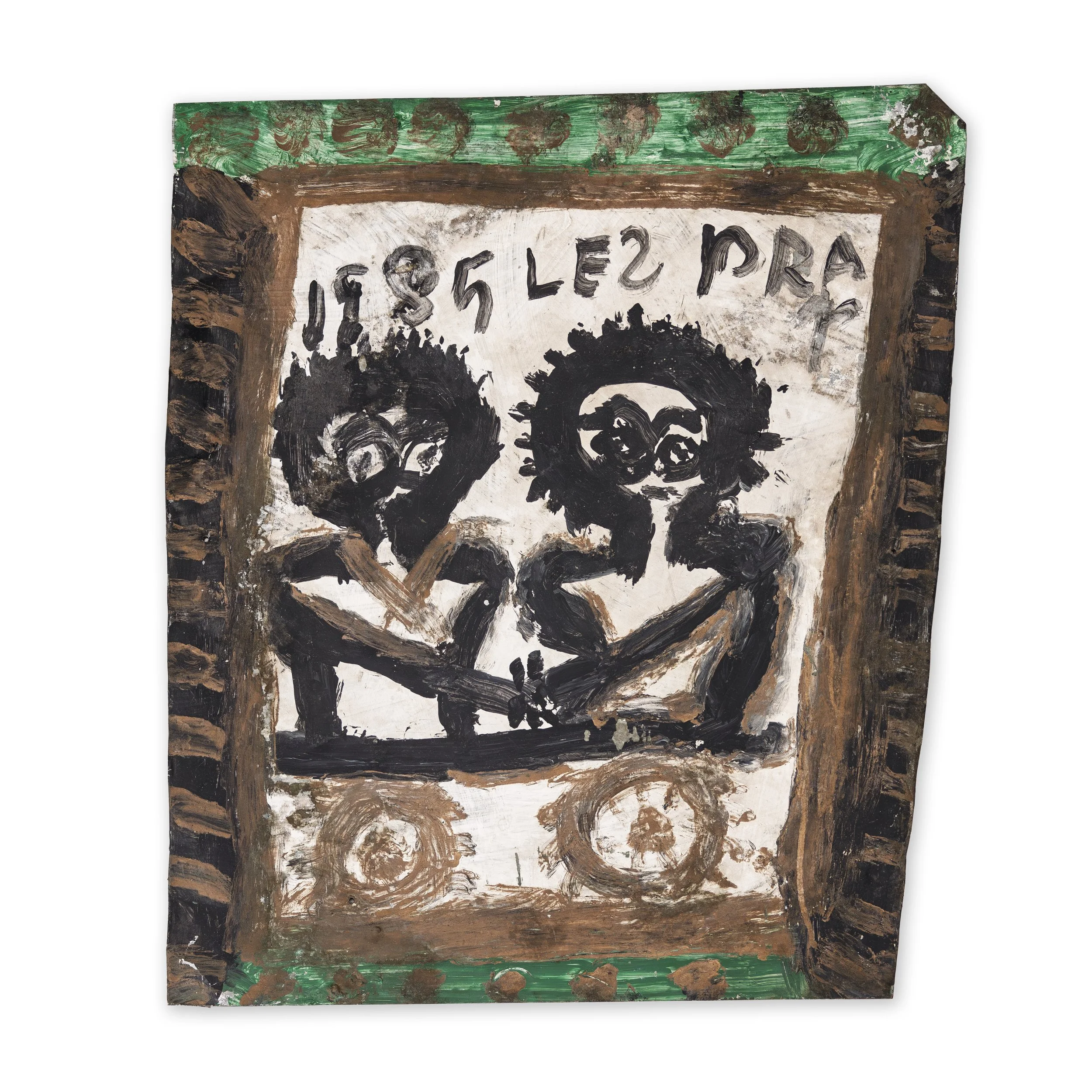

Mary Tillman Smith was a self-taught painter of the American South who lived and worked in Mississippi her entire life. She created bold, colorful, and expressive paintings, using house paint on found tin or wood. Her work consists of highly stylized figures in strong colors, often with animating dots and dashes, alongside sometimes cryptic abstract texts laid upon monochrome contrasting background colors. Her work is shown throughout the world and is in the permanent collections of museums such as the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, D.C.), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, New York), the High Museum of Art (Atlanta, Georgia), the de Young Museum of Art (San Francisco, California), the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston, Texas), and the Birmingham Museum of Art (Birmingham, Alabama), among others. She is considered one of the great Southern self-taught artists, a group that includes Thornton Dial, Purvis Young, and Nellie Mae Rowe, to name only a few.

-

From the late 1960s through the 1970s, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., a remarkable cultural phenomenon unfolded in the southern United States yet went almost unnoticed. As if in unspoken response to a trumpet’s reveille, black people throughout the region came out from their houses, or factories, or in from the fields, and intensified their creation of artistic environments, or “yard shows,” so the outside world could see what had been previously expressed in secrecy inside and behind their residences. It had been there for centuries, this yard-show tradition, but almost no one outside the culture knew about it, this not-for-our-eyes cubism, fauvism, expressionism, surrealism, dada, abstract expressionism, pop, minimalism, graffiti, postmodern, neo-this, neo-that, neo-everything. Or proto-everything.

Smith was born Mary Tillman in 1904 in Copiah County, southern Mississippi, and grew up in the town of Martinville. She was the third of thirteen children. Her sister Elizabeth, the seventh child, describes those times: “We helped our father on the farm. We struggled on the land. We were raising cabbages, tomatoes, beans, stuff like that. We wrapped vegetables, packed them in boxes, shipped them. The family was working sharecropping, but our father bought his own place later on.”

Smith left home in her teens and entered into a brief marriage with a man named Gus Williams. The marriage lasted two months; after she caught him deceiving her, she left. “Anybody that tells that big a lie, I can’t stay with,” she told her family. She then went to work for a white family in Wesson, a few miles from Martinville. She lived in their house. She washed, cooked, and cleaned for them. After a few years there, she met and married John Smith, a sharecropper, and moved into his cottage on two acres of potatoes and peanuts. This marriage, like the first one, ended abruptly. When her husband’s year-end settlement was given to him, Mary Smith realized that the amount was drastically insufficient. She had meticulously recorded all the data concerning her husband’s labor. She told his boss, “We only got $17. You must have made a mistake. $1,154 supposed to come to us.” The boss ordered John Smith to rid himself of his spouse. John Smith acquiesced, packing Mary Smith’s belongings and sending her away. The boss brought him a new “wife,” and Mary Smith, in her thirties, moved to Hazlehurst, the largest town in the immediate area, to figure out her life.

In Hazlehurst, Smith worked as a domestic servant and gave birth to her only child, Sheridan L. “Jay Bird” Major, in 1941. Though she did not marry the father, he built her a house where she lived and raised their son. That house - a neat wood bungalow on a one-acre lot, sitting beside the main road through Hazlehurst - gave Mary T. Smith a new beginning. She was finally independent - at least to the extent that she had a home, work when she wanted it, and access to fields for growing all the vegetables she needed.

Near her house was a garbage dump, piled with discarded corrugated tin - strong, interesting material, free for the taking. Smith dragged home piece after piece of it, day after day, and with an ax, she split off strip after strip. She then split some of the strips into smaller strips and some of the smaller strips into even smaller ones, and with the deft improvisational sense of the best quilter or the best assemblage sculptor or jazz musician or poet, she marked her space with a fence of whitewashed corrugated tin strips, providing herself with the ever-presence of a continuously running jazz symphony or epic poem, or the world’s longest strip quilt. Like Penelope weaving her never-ending tapestry while awaiting the return of Odysseus, this was a woman ready to make a statement.

She had additional ideas for the area within the fence. Like a landscape architect, she created spaces with spaces, unpredictable, surprising, metaphorical, symbolic spaces, some chaotic, some studiously ordered, some color-coordinated, some manicured; they were Mary Smith’s version of the world, the world she had perfectly figured out, the sacred and profane world of Copiah County and planet Earth.

Gradually Smith’s space began to fill with art. She had earlier constructed a series of outbuildings and furnishings within the space–doghouses, storage huts, tables, and benches, and later a de facto “studio” in which to work and display her most recent paintings. The buildings themselves were works of art, wood and tin sculptures usually painted with inventive patterns and designs.

Smith designed the yard to fulfill all her needs. Her hearing had worsened as she grew older, and she was uncomfortable going out into Hazlehurst. Elizabeth Alexander described her sister Mary’s hardship: “She used to go to church on Sundays, and go into town sometime, but she started slowing down from a going places because people would always look at her like she was crazy. That made her feel bad.” In 1986 Smith said, “I don’t go nowhere no more. I can’t hear nothing. I don’t need nothing. I got it all here. My church. The Lord Jesus.”

Painted and written scripts and slogans were also an integral part of the yard. Though Smith was capable of legible printing and cursive writing, she wrote on many of her paintings with inscriptions that were seemingly unintelligible. This may have been an attempt to play into the town’s perception of her as ignorant or crazy, thereby affording her a degree of privacy and, hence, security. The inscriptions, especially those on religious paintings, seem to belong to a purposeful and meaningful system, and like John B. Murray with his quasi-writing, Smith probably understood thoroughly her invented words. In other cases, her “writing” seems simply an improvisational almost formalist use of letters and script as elements of design, a technique employed for centuries by African American quilters, for example.